[Chinmayanand Chivukula is an Advocate based in Hyderabad]

The ‘group of companies’ doctrine originated in France in the ICC case of Dow Chemical France v. Isover Saint Gobain. In essence, it requires non-signatories to be bound by an arbitration agreement if such mutual intention can be made out amongst the entities within a group of companies. The purpose of the doctrine is to deconstruct commercial arrangements and complex business structures to deduce the role of the parent company and its subsidiaries in the conclusion, performance, and termination of contracts. That the ‘group of companies’ doctrine dilutes the foundational principle of consent in arbitration is well-known. However, the difference between civil law and common law judicial systems means that what may be a legitimate application of the doctrine in France may not necessarily be compatible with Indian law and jurisprudence.

The ‘group of companies’ doctrine has assumed renewed significance in India due to the reliance placed on it by the emergency arbitrator in the Amazon-Future arbitration. Its usage was reaffirmed by the Delhi High Court while hearing connected proceedings arising out of the dispute. It is in this context that I raise two arguments in this post: (a) Indian Courts should factor in an investigation into a non-signatory’s implied consent to be bound by the arbitration agreement when applying the ‘group of companies’ doctrine, and (b) section 8 of India’s Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“Act”) cannot be relied on to compel a reluctant non-signatory to arbitrate.

A Primer on the Amazon-Future Dispute

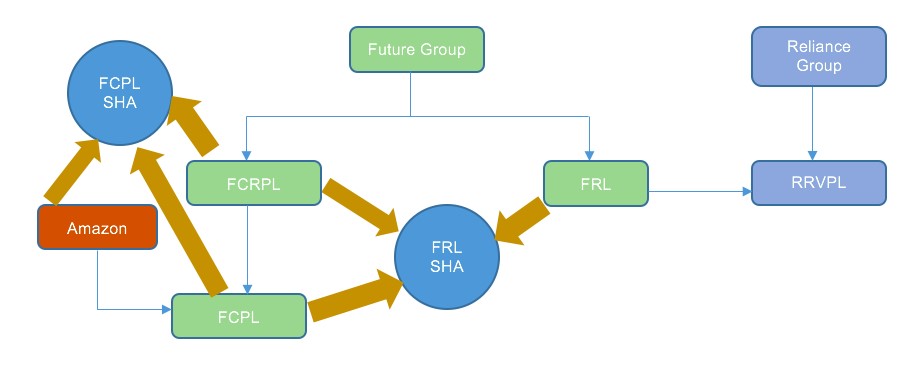

Future Coupons Pvt. Ltd. (“FCPL”), Future Corporate Resources Pvt. Ltd. (“FCRPL”), and Future Retail Ltd. (“FRL”) are members of the Future Group owned and controlled by Mr. Kishore Biyani. FCPL was a wholly-owned subsidiary of FCRPL. By way of a Shareholders’ Agreement between FCPL, FCRPL and FRL (the “FRL SHA”), FCPL acquired special rights in the management of FRL. Interested in FCPL’s rights concerning FRL, Amazon.com Investment Holdings LLC invested INR 1431 crores in exchange for a 49% stake in FCPL. The remaining 51% was retained with FCRPL. A subsequent Shareholders’ Agreement was signed between Amazon, FCPL and FCRPL (the “FCPL SHA”). One of the significant rights in the FCPL SHA was that the prior consent of Amazon would be required in any matter where FCPL’s consent was necessary under the FRL SHA, including “any sale, divestment, transfer, disposal, etc. of retail outlets across various formats operated by FRL”. FRL was not party to the FCPL SHA.

The dispute arose when, in the wake of the pandemic, FRL found itself in a dire financial situation, with banks and financial institutions knocking on its doors. Reliance Retail Ventures Pvt. Ltd. (“RRVPL”), part of the Reliance Industries group of companies headed by Mr. Mukesh Ambani, offered to acquire FRL for a consideration of INR 24,713 crores. Mr. Kishore Biyani agreed, and the deal was set in motion. However, Mr. Mukesh Ambani was a ‘Restricted Person’ under the FRL SHA, i.e., a person to whom FRL’s assets could never be alienated, and especially not without Amazon’s consent. Amazon initiated emergency arbitration proceedings in Singapore under the FCPL SHA, where it argued that the deal between FRL and RRVPL was initiated without its consent and in contravention of the rights granted to it in the FCPL SHA. Amazon sought injunctive relief against FCPL and FRL to halt the transaction between RRVPL and FRL.

The emergency arbitrator granted this relief, and relied on the ‘group of companies’ doctrine to bind FRL to the arbitration agreement in the FCPL SHA, despite it not being a party to that agreement. In the proceedings before the Delhi High Court for the enforcement of the emergency award, the Court upheld the reasoning of the arbitrator and justified the joinder of FRL under section 8 of the Act.

Critical Analysis

Guarding the Sanctity of Consent

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the ‘group of companies’ doctrine dilutes the contours of consent in arbitration. The focus on the ‘single economic reality’ of entities within a group of companies detracts from the crux of the matter: has the non-signatory consented (expressly or impliedly) to be bound by the arbitration agreement?

This could be an unintended outcome of the doctrine’s civil law heritage, where the adjudicator remains in complete control of the proceedings. The consequence is that the question of whether parties to the dispute have consented to arbitrate or not fast loses relevance in the adjudicator’s effort to determine the ‘ultimate truth’. For instance, in Orri v. Société des Lubrifiants Elf Aquitaine [1992] Jur Fr 95 (11 January 1990), the Paris Court of Appeal held that an arbitration clause can be extended to non-signatories if the parties’ “contractual situation, their activities and the normal commercial relations existing between the parties allow it to be presumed that they have accepted the arbitration clause of which they knew the existence and scope, even though they were not signatories of the contract containing it.”.

This is fundamentally incompatible with the shape and form of the common law justice system where the adjudicator plays a passive role in the proceedings. The intention of the parties remains front and centre during the proceedings. I argue that to respect the consensual nature of arbitration, the treatment of the ‘group of companies’ doctrine in India cannot (and should not) be separated from its civil law origins.

The ‘group of companies’ doctrine was first applied by the Supreme Court of India in Chloro Controls (I) P. Ltd. v. Severn Trent Water Purification Inc., where the Court had held that non-signatories to an arbitration agreement could be permitted to join an arbitration under this doctrine. Importantly, the Court stressed that the intention of the parties to include the non-signatory is essential. The existence of consent, on whose basis intention is established, has not necessarily played the most important role in subsequent cases. For instance, in Cheran Properties Limited v. Kasturi and Sons Limited, the Supreme Court expanded the application of this doctrine to hold that a non-signatory can even be bound by the arbitral award.

While judicial decisions in India on the interplay between consent and the doctrine are few and far between, other common law jurisdictions have expressed reservations with the doctrine. Courts in Singapore and the United Kingdom share this view, with the High Court of Singapore noting that enforcing an arbitral award against a non-signatory “would be anathema to the internal logic of the consensual basis of an agreement to arbitrate”. This reasoning could be extended to joining a reluctant non-signatory to an arbitration as well, a situation where a more analytic rigour and hesitation is warranted.

Bearing in this mind, courts in India ought to tread carefully in relying on the ‘group of companies’ doctrine to extend an arbitration agreement to a non-signatory. Mere membership of a group of companies ought not to be sufficient. In addition to analysing the role of the non-signatory in the performance of the contract, courts must enquire into the modes through which the non-signatory expressed its consent to arbitrate, if at all. This can be derived from basic principles of contract law and company law. For instance, an English court in Peterson Farms v. C&M Farming Ltd. utilised principles of agency and estoppel to determine whether an award could extend to non-signatories. The Delhi High Court in Shapoorji Pallonji and Co. Pvt. Ltd. v. Rattan India Power Ltd. joined a non-signatory parent company to an arbitration between a signatory subsidiary and another party by applying the ‘corporate veil’ theory within the ‘group of companies’ doctrine.

Thus, I believe that the reliance on contract and company law principles will guide the operation of the ‘group of companies’ doctrine in a holistic manner, and shift the emphasis from the role of the non-signatory within a corporate structure to the nature of its consent (or lack thereof) to arbitrate. Had such an analysis been conducted in the Amazon-Future dispute, the outcome could have been quite different.

Section 8: “Person Claiming Through or Under a Party”

My second argument is that the ‘group of companies’ doctrine cannot be used to compel a non-signatory to arbitrate under Section 8 of the Act. Section 8 of provides for the courts’ power to refer parties to arbitration where there is an arbitration agreement. Prior to its amendment in 2015, the section provided that only a party to an arbitration agreement could apply to the court to refer a matter pending before it to arbitration. Section 8 was amended in 2015 to bring it in line with similar provisions in Part II of the Act, i.e., sections 45 and 54, which contemplate a like power for arbitration under the New York Convention and the Geneva Convention respectively. The 2015 amendment made it possible for “a party to the arbitration agreement or any person claiming through or under him” to apply to the Court to join an arbitration.

It was this phrase that shaped the landmark decision of the Supreme Court in Chloro Controls v. Severn Trent. Within the context of section 45 of the Act, the Supreme Court applied the ‘group of companies’ doctrine to hold that non-signatories to an arbitration agreement could be permitted to voluntarily join an arbitration as “persons claiming through or under” a party. The Court opined that the Parliament intended to encourage arbitration by widening the ambit of those who could apply to the court to commence an arbitration in a pending matter. While the UNCITRAL Model Law does not include such language that would extend the arbitration agreement to a non-signatory, it is possible that the Parliament acted in accordance with international cues such as the ICC Dow Chemicals decision and the provisions of the English Arbitration Act 1996.

Section 82(2) of the English Arbitration Act 1996 provides that references to a party to an arbitration agreement should be treated as including “any person claiming under or through a party to the agreement”. English Courts have approached this with circumspection: City of London v. Sancheti, a court held that “a mere legal or commercial connection” to the relevant agreements “is not sufficient” to bind a non-signatory claiming “through or under” a party to an arbitration agreement. Similarly, the Delhi High Court also commented that “binding a non-signatory to arbitrate (against its will) is significantly more difficult than allowing a non-signatory to voluntarily invoke or participate in an arbitration through or under a signatory.”

I submit that the Delhi High Court erred in compelling FRL to arbitrate under section 8. FRL could not have been construed as a “person claiming through or under” a party to the arbitration agreement as it simply did not claim to join the arbitration at all. In fact, FRL consistently resisted joining the arbitration between Amazon and FCPL. Thus, the Delhi High Court could not have used Section 8 as a means to apply the ‘group of companies’ doctrine because FRL, as a reluctant non-signatory, did not meet the criteria to trigger the exercise of powers under that Section.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court concluded the judgement in Chloro Controls on a cautionary note: that the discretionary power of the court to join a non-signatory to an arbitration should be “exercised in exceptional, limiting, befitting and cases of necessity and very cautiously” (sic). It now remains to be seen whether, and how, Indian courts heed this advice.

– Chinmayanand Chivukula