[Shubham Sancheti is a 4th year B.A., LL.B. (Hons.) student at NALSAR University of Law in Hyderabad]

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) recently availed an opportunity to interpret regulation 37(6) of the SEBI (Listing Obligation and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 (“LODR Regulations”). It provided an interesting yet contestable interpretation of the regulation insofar as the exemption to a “wholly owned subsidiary” is concerned.

SEBI inserted clause 6 to regulation 37 of the LODR Regulations by the way of an amendment which exempts a company from pre-filing a draft scheme of arrangement with the stock exchanges, before it is filed with the Court or tribunal, if any wholly owned subsidiary is to be merged with the holding company. Until this amendment, Regulation 37 was applicable to every listed company proposing any kind of scheme of arrangement including ones with its wholly owned subsidiaries. The erstwhile regulation required the listed companies to fulfill all the compliances mentioned thereunder, including obtaining the observation letter or no-objection letter from the stock exchanges. SEBI’s intent behind exempting such compliances was to further the idea of fast track merger in accordance with section 233 of the Companies Act, 2013 because obtaining an observation letter or no-objection certificate or from the stock Exchanges would take substantial amount of time, which defeated the purpose of section 233. However, this explicit exemption from the compliances does not grant exemption from filing to the stock exchanges for disclosure purpose, which is required to be done on a post facto basis.

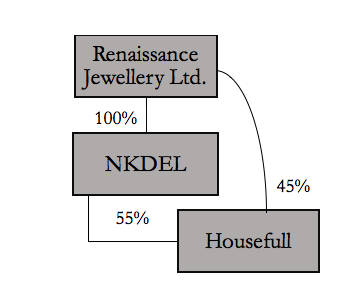

In an informal guidance issued by SEBI in the matter of Renaissance Jewellery Ltd., the company sought an interpretation of the exemption under the regulation 37. The structure of the company was such that Renaissance owned a wholly owned subsidiary N Kumar Diamond Exports Ltd. ( “NKDEL”) which in turn had a subsidiary Housefull International Ltd. in which NKDEL owned 55% of equity. The remaining 45% of Housefull’s shares were owned by Renaissance. To represent it pictorially:

By a letter seeking informal guidance, Renaissance expressed it desire to merge NKDEL and Housefull into itself and sought an exemption under regulation 37(6) of the LODR. Interestingly, SEBI stated that since the entire share capital of the Housefull is owned either directly or “indirectly” (through NKDEL) by Renaissance, Housefull may be considered as a wholly owned subsidiary of Renaissance. In other words, a subsidiary of the wholly owned subsidiary was also considered to be a wholly owned subsidiary of the holding company merely because the holding company owned the remaining equity of the subsidiary. Notwithstanding the fact that SEBI clarified in the letter that this interpretation is only valid for the purpose of exemption under the LODR, this interpretation may have consequences as discussed below.

The Companies Act, 2013 or rules thereunder do not define “wholly owned subsidiary”, but they have not refrained from granting relaxations to such companies when it comes to related party transactions,[1] appointment of independent directors[2] and loans provided by a company.[3] A definition of “wholly owned subsidiary” can be found under the Foreign Exchange Management (Transfer or Issue of Any Foreign Security) (Amendment) Regulations, 2004. It states-

“Wholly Owned Subsidiary” means a foreign entity formed, registered or incorporated in accordance with the laws and regulations of the host country, whose entire capital is held by the Indian party.

This definition may be of no significance due to the trite law that a word or expression defined in one statute cannot be of any guidance to interpret the same word or expression in another statute. However, such definitions may be of some guidance if the two legislations are pari materia.[4] Since by the LODR and FEMA 2004 the respective regulatory authorities regulate the transfer of securities, irrespective of the fact that the latter pertains to foreign entities, the objective of the two statutes appears may be comparable. The statutes are pari materia if they relate to the same person or thing or to the same class of persons or things.[5] By the aforesaid interpretation, a company can be said to be a wholly owned subsidiary of another, only if the latter owns its entire capital.

Notwithstanding the fact that explanation (a) to section 2(87) of the Companies Act, 2013 states that a subsidiary of a subsidiary will be a subsidiary of the holding company, it cannot be logically deduced that a subsidiary of the wholly owned subsidiary will be a wholly owned subsidiary as well. If we take an inverse proposition, a wholly owned subsidiary of the subsidiary of a company does not become a wholly owned subsidiary of the holding company; then the current exemption granted to Renaissance does not hold the ground either. To further substantiate the point, the Supreme Court in Vodafone International Holdings B.V. v. Union of India defined a wholly owned subsidiary as one where all of the voting stock is owned by the holding company.[6] In the matter of Renaissance, it will not be incorrect to say that Renaissance’s effective shareholding in the Housefull was 100%, but that does not necessarily make Housefull a wholly owned subsidiary of the Renaissance.

Last but certainly not the least, another problem which may consequentially arise with respect to such interpretation of regulation 37(6) would be under the recent Companies (Restriction on Number of Layers) Rules, 2017. The second proviso to rule 2 excludes the first layer of the wholly owned subsidiary/subsidiaries while counting the layers of subsidiaries of a company. By SEBI’s interpretation of regulation 37(6) of the LODR Regulations, if the Housefull is considered to be a wholly owned subsidiary of Renaissance, it would have to be omitted while being counted as a layer of Renaissance’s subsidiaries. This is one problem with the literal interpretation of the Companies (Restriction on Number of Layers) Rules, which has also been discussed here. Furthermore, this interpretation of SEBI may call for an exemption when a wholly owned foreign subsidiary merges with the holding Indian listed company.

Conclusion

The problem pertaining to evasion of taxes and formation of shell companies through subsidiaries was recognized by the Supreme Court in Vodafone. To overcome the same, the legislature enacted the rules to restrict the layers of subsidiary a company may have. However, the exemptions granted thereunder may not nip such problems in the bud if SEBI’s interpretation through this informal guidance is given effect to. Even by limiting such interpretation to the LODR, SEBI did not seem to have eschewed the aforementioned consequences. Hence, SEBI and other regulators must have a uniform interpretation throughout to avoid the misuse of corporate structures in India.

– Shubham Sancheti

[1] See rule 15 of the Companies (Meeting of Board and its Powers) Rules, 2014.

[2] See rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014.

[3] See rule 11 of the Companies (Meeting of Board and its Powers) Rules, 2014.

[4] See Sri Jagatram Ahuja vs The Commissioner of Gift Tax, AIR 2000 SC 3195.

[5] United Society v. Eagle Bank, (1829) 7 Conn. 475.

[6] (2012) 6 SCC 613.